Protecting & saving an iconic species

Content last updated July 25, 2024. Photo in header by John Burgess, Press Democrat

Populations plummet

White abalone are apparently the most delicious of the seven North American abalone species, which is why they were targeted in the fishery. Humans fished about 99% of them in just about 10 years in the 1970s. Unfortunately, abalone are terrible at long-distance relationships, and their densities were reduced to the point that animals were too far from one another for the tiny eggs and sperm they release into the water to find each other. This meant that populations could not rebound on their own, despite the 1996 closure of commercial and recreational harvest.

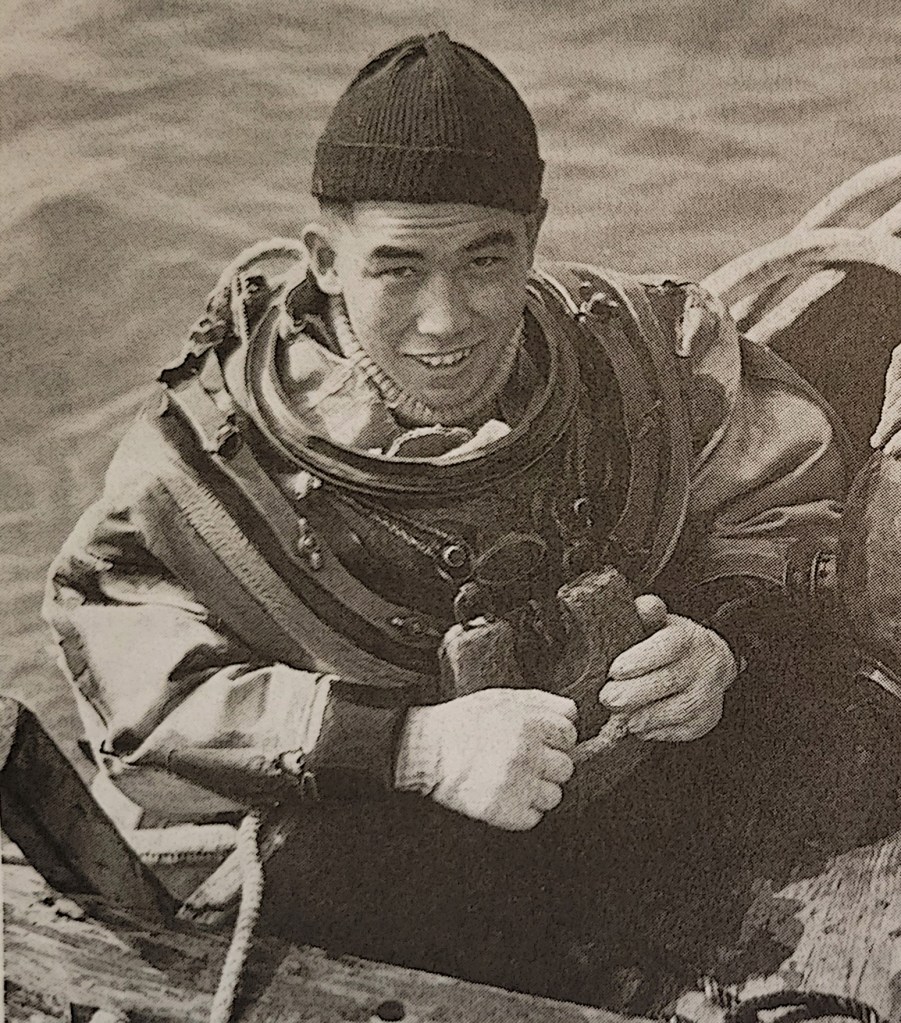

1939

Japanese American diver Roy Hattori brought the first white abalone specimens to the attention of mainstream science, collecting from a depth of 60 feet near Point Conception. Hear from Mr. Hattori himself here and more about his collection of white abalone here .

Image source: Vileisis, A. (2020). Abalone. Oregon State University Press Hear from Roy Hattori’s grandson, Tommy Hattori, here:

1965

White abalone were targeted by commercial fishery. Prized as the most tender of the abalone species on the West Coast of North America, they were said to fetch the highest price at market.

1972

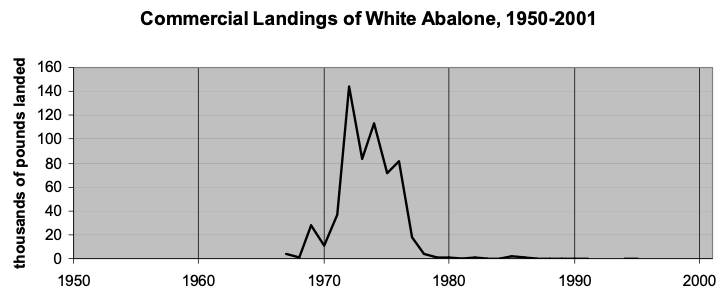

White abalone landings by commercial fishery peaked at 144,000 pounds in one year.

1981

Annual commercial landings plummeted to 280 pounds in 1981 and averaged only 300 pounds from 1991 through 1994 ( Davis et. al 2011 ).

1990s

Multiple white abalone search efforts were conducted by California Department of Fish and Game (Wildlife) and the National Parks Service via diving and submarine, searching tens of thousands square acres of suitable habitat, finding very few abalone all miles apart. ( Davis et. al 2011 ).

1996

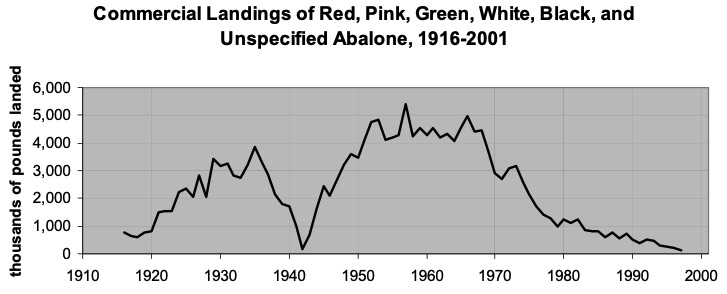

California Fish and Game Commission closed both commercial and recreational white abalone fisheries. As seen in the graph below, by 1996, landings had fallen to about 229,500 pounds, just 4% of the fishery’s peak landings of 5.4 million pounds. (CDFW)

1997

Fisheries for all abalone species were closed south of San Francisco.

1998

The White Abalone Restoration Consortium was established to develop a recovery strategy for white abalone.

Setting the Stage for Recovery

When white abalone recovery efforts began, there was a thought that they would be a relatively straightforward species to save. Not only are there abalone off the coast of every continent except for Antarctica, there are also abalone farms on every continent except for Antarctica. Humans were really good at growing abalone in captivity. Furthermore, the white abalone’s habitat – deep, cool waters off the coast of Southern California, USA down into Baja California, Mexico – was relatively intact. If enough white abalone could be produced in captivity and placed in the ocean, the species could be saved.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries deemed that captive breeding and “outplanting” (i.e., placing captive-origin animals into the ocean) was the only way to save the species. To jumpstart the White Abalone Captive Breeding Program, divers collected animals from the remnant population to breed in a land-based facility.

2000

The first 17 white abalone were collected from a remnant population and brought to a land-based facility to breed.

2001

A successful spawning resulted in millions of embryos, 100,000 of which survived through sensitive early life stages. A few months later, the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service listed white abalone as endangered species, making them the first marine invertebrate listed. A recovery plan was developed.

2002

An emerging disease, withering syndrome hit the captive white abalone population, reducing the captive population by nearly 95%.

2003

The last successful spawning attempt for nearly a decade occurred. From 2004-2011, scientists were unsuccessful at getting abalone to spawn, in part due to this new disease, withering syndrome.

Disease Poses New Challenges

The more than 100,000 juvenile white abalone produced in the first spawning vastly outnumbered the likely abundance of what remained in the wild. Unfortunately, when those animals were around a year old, approximately 95% of them died from disease.

The disease that plagued early white abalone captive breeding efforts was called Withering Syndrome and was caused by a bacterium that affected the esophagus of the abalone. The top image shows a healthy red abalone, with a foot that completely fills its shell. The bottom red abalone has a shrunken foot due to Withering Syndrome. This disease is interesting because it is temperature-dependent. In cool water (<18°C/65°F), abalone can be infected with the bacterium and appear asymptomatic; however, when waters warm, the abalone stop eating and instead digest their foot mussel, which “withers” away.

In 2001, scientists and restoration practitioners were beginning to understand the causes and consequences of Withering Syndrome, and they did not yet understand how devastating it was for white abalone, nor was there anything they could do to treat it. In the subsequent decade, scientists at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the University of Washington began to understand more about the disease, and even developed an antibiotic bath treatment to rid infected abalone of the bacterium. With newly healthy parents and offspring, the White Abalone Captive Breeding Program was again poised for success.

2008

The 50 remaining captive white abalone were distributed among facilities throughout California.

2011

UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory (UCD-BML) became the Endangered Species Act (ESA) permit holder for caring for and breeding white abalone in captivity after years of struggle with production. But just like the saying, “Don’t keep all of your eggs in one basket,” it is unwise to keep all endangered animals in one facility. Partners not only distribute possible risks to the captive population, they also provide experiences and expertise that one facility alone could not accomplish. See our Partners page for our current team.

2012

The first successful spawning attempt of white abalone in nearly a decade occurred on June 14, 2012.

Of the 18 white abalone bathing in hydrogen peroxide solution on June 14th 2012, two females spawned very few eggs. A ripe female white abalone should spawn millions of eggs, but these two females released only ~300,000 eggs each. The one male that spawned only released a minuscule amount of sperm. In fact, its spawn was so fleeting, the scientists almost missed it! Though the sperm was scarce, it was enough to fertilize approximately half of the eggs that were spawned. About 20 animals from the spawn survived to be one year old. While only a few new white abalone resulted, successfully reproducing white abalone in captivity for the first time in nearly a decade was a huge leap forward for the recovery program!

The subsequent years would focus on increasing the abundance and reliability of white abalone reproduction. Since then, production has increased exponentially!

Learn more about how the program has advanced captive breeding, as well as the very first release of white abalone into the ocean in the “What We Do” pages.

2015 – Species in the Spotlight

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration launched a Species in the Spotlight campaign in March 2015 to bring attention to and marshal resources for marine species at imminent risk of extinction. White abalone was first and only invertebrate to become a NOAA Spotlight Species.

2016 – New Broodstock Enter the Program

Saving a species as close to the brink of extinction as white abalone requires putting as many white abalone into the ocean as quickly as possible, but paying attention to genetics is also important. As captive production increased and became more reliable, concerns about the genetic diversity of the captive population lingered.

The recovery team wanted to represent what genetic diversity was left in the remnant wild population as closely as possible. They also wanted to maximize genetic variation to make it more likely that outplanted white abalone could deal with challenges like climate change.

In October 2016, the first of a round of new wild white abalone was collected by NOAA Fisheries and California Department of Fish and Wildlife scientists. The team brought more wild-origin white abalone into the Captive Breeding Program over the next three years.

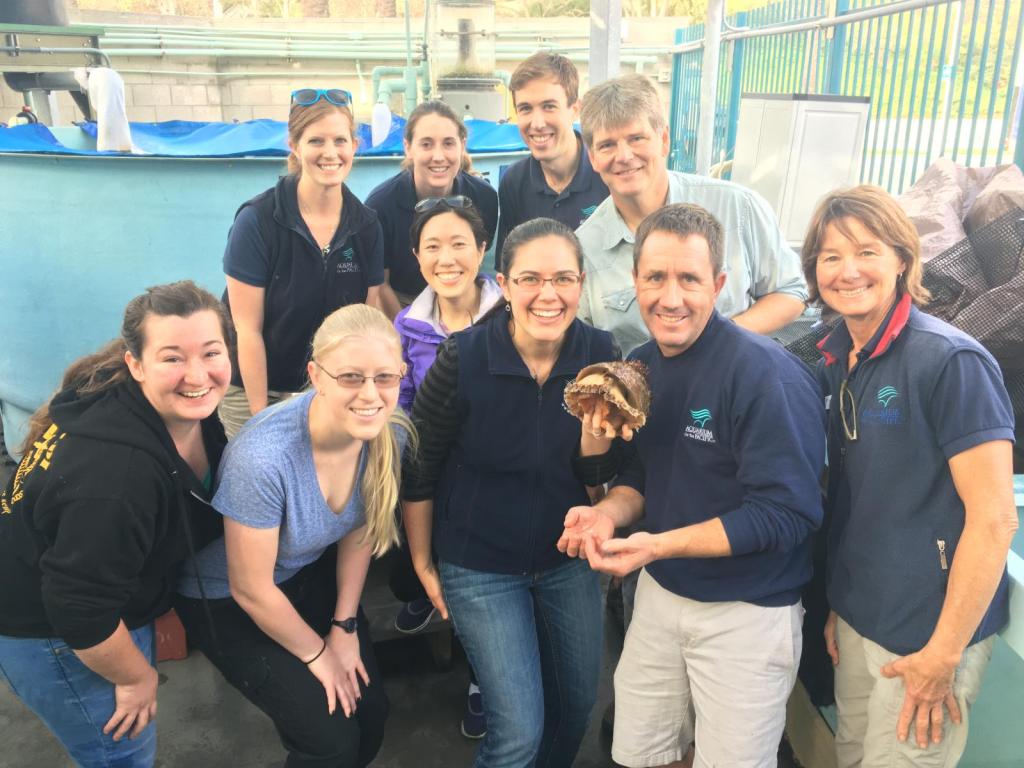

Introducing a wild white abalone to his species recovery team. 2017

A white abalone collected from the wild spawned, successfully introducing new genes into the program for the first time in 14 years!

A female white abalone releases eggs. This abalone’s shell is covered with a waxing treatment to help remove harmful shell-boring organisms.

2018

While scientists in the Captive Breeding Program continued to find ways to increase production other members of the Recovery Team, including NOAA Fisheries, California Department of Fish and Wildlife , Paua Marine Research Group , Aquarium of the Pacific , and The Bay Foundation led research to identify the best methods for placing captive-origin white abalone to the wild using red abalone as a surrogate species.

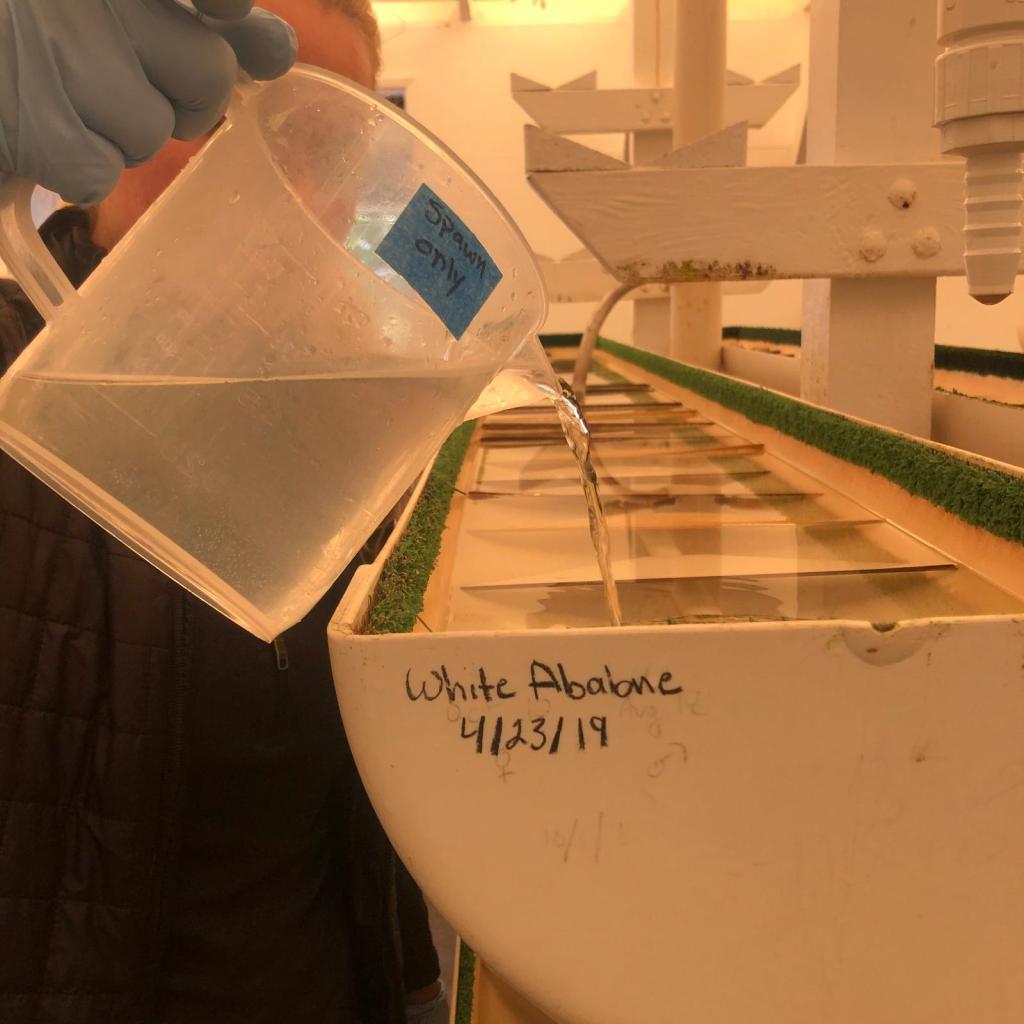

2019 – A massive spawn & embryo shuffle!

When a white abalone surprised the team with over 20 million eggs – a number far beyond what anyone expected – partners throughout California jumped into action to help house the resulting embryos and larvae. The slideshow below shows their journey.

2019 – White Abalone are released into the ocean for the first time

The first white abalone outplanting – where captive-origin white abalone were placed into the wild – occurred in October 2019. This marked a pivotal new phase of the species’ recovery efforts.

See this page to learn more about this monumental event.

A Brighter Road to Recovery

The White Abalone Captive Breeding Program moved to UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory in 2011, and includes many more partners that help in the captive production, reintroduction, and education and outreach parts of restoring this species. Explore this site to learn more about the Captive Breeding Program and our partners.

Once a warning of what can happen when fishing demand surpasses sustainability, white abalone have also become a symbol of what can happen when we come together to right a wrong, rebuild a population, and grow a sustainable future for an endangered species. Gifts support the White Abalone Captive Breeding Program at UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, including efforts to breed, raise, and return white abalone back to their ocean home.

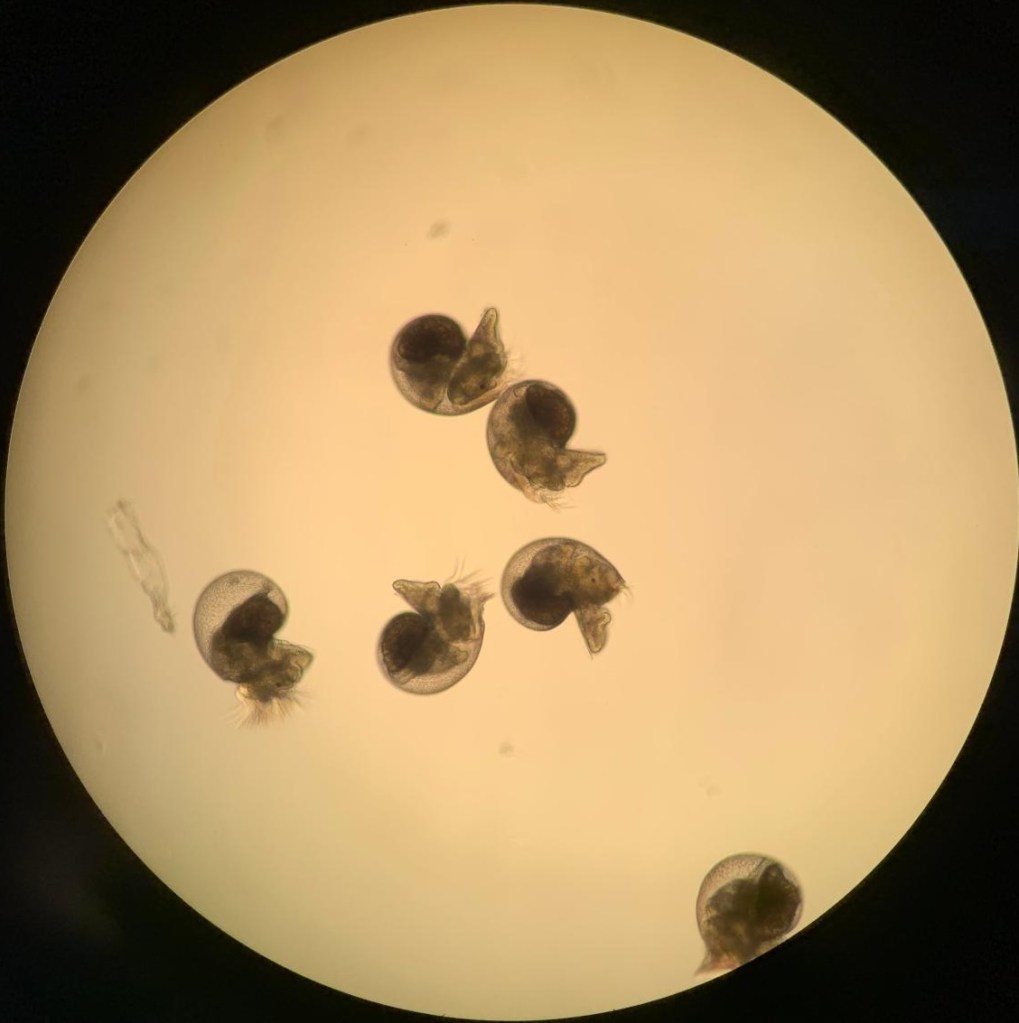

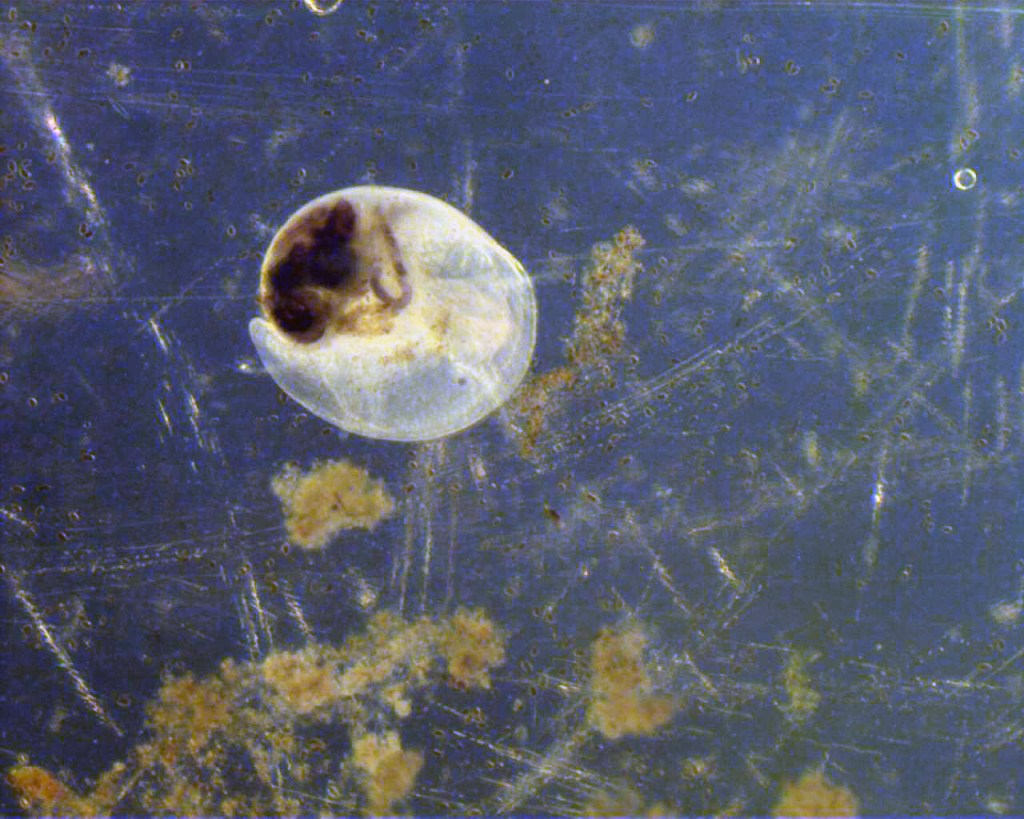

A two-month-old white abalone grazes on a film of diatoms. At this age, its shell is translucent. The dark mass toward its apex is its gut, and the black dot under the shell, just to the right of the head is one of its eyes. In about one more month, when this animal has grown about 1 millimeter longer, it will begin to form its first respiratory pore (one of the holes in the shell that sits over the animal’s gills).