Abalone are a group of marine snails that are distributed around the world’s coastal oceans, particularly in rocky reef habitat. White abalone (Haliotis sorenseni) is one of seven species of abalone in North America. (Photo above by John Burgess)

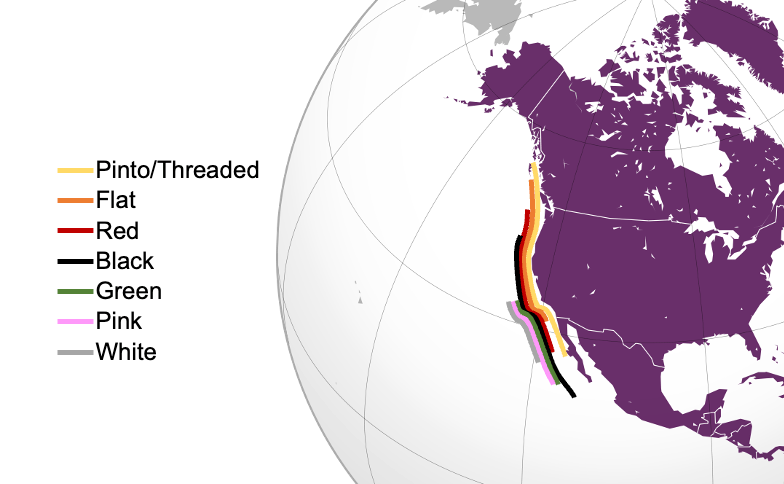

North American abalone distribution. White abalone can be found from Point Conception south through Baja California. They are the deepest water species, preferring depths around 50-180 ft.

Biology

White abalone are giant marine snails, with an oval-shaped shell. They have a strong muscular “foot” that allows them to adhere to their rocky reef habitat and crawl along the ocean floor. Fairly sedentary, they also use their foot to capture kelp and other algae as it drifts by.

The top of an abalone shell contains a row of holes, called respiratory pores. Abalone use these holes to breath (their gills are located just underneath the pores), to excrete waste, and to expel eggs and sperm. They have a mouth at the anterior end, just behind their adorable eyes. White abalone are herbivores, preferring to eat algae including the iconic giant kelp. They get their name from the color of their mantle (or soft tissue) that peaks out through those holes, which looks white, even at depth. Their foot tissue and epipodia (the frilly bits along their sides) range from bright orange to beige.

Endangered Status

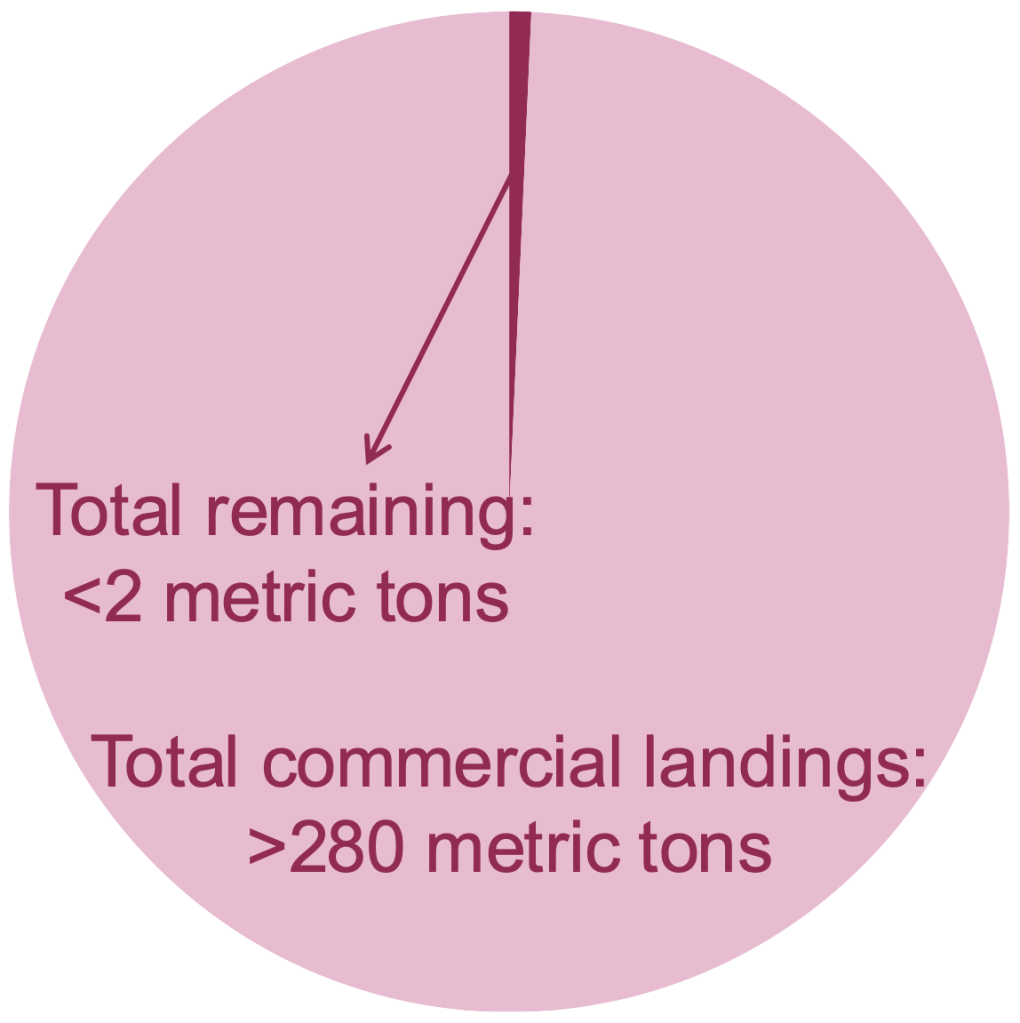

White abalone is considered Endangered throughout its range. Commercial fishing removed over 280 metric tons of white abalone from the ocean. Less than 2 metric tons (approximately 1,600-2,500 animals) remained. By the time the commercial fishery closed in 1997, the damage had been done, and over 99% of the species was lost in just one decade. Abalone are broadcast spawners, which means that males and females release sperm and eggs into the water column, where they will join together and form an embryo. For this to happen, abalone need to be near another white abalone of the opposite sex. Otherwise, the gametes would be too dilute to lead to successful fertilization.

You see, white abalone are terrible at long-distance relationships. Overfishing the species down to less than 1% of its historical abundance meant that the few animals left were too far apart to reproduce in the wild. If scientists didn’t intervene, the species would most likely continue to decline towards extinction. This is where we come in.

In 2001, after white abalone became the first marine invertebrate to be listed as an endangered species, captive breeding efforts began in earnest to restore this iconic species.

Click here to learn more about the white abalone’s Road to Recovery.